Puppets on a (massive) swing?

“It don’t mean a thing if you ain’t got that swing”. The UK Government has moved from setting a budget with an apparent £55bn giveaway to one that ostensibly claws back £60bn in a furious attempt to ‘balance the books’ in just five weeks. We’re not the only ones feeling discombobulated – but is the Government doing the right thing and what does it mean for the UK economy?

The Chancellor’s search for assets to shore up the nation’s balance sheet continues

Our initial take on the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement considers both the announcement itself and the long-awaited Office of Budget Responsibility’s forecast, which is incredibly revealing as to the real state of the UK economy. We’re undoubtedly in for a rough ride folks, but it could have been a lot worse….

THE GOOD (AT A PUSH)

Let’s get the obvious point out of the way – at least it isn’t founded on fantasy economics. We rightly panned the previous Chancellor’s mini-budget which appeared to both ignore prevailing economic conditions and sub-par economic growth over the past twelve years (as per the graph on the right-hand side), concocting a brilliant mix of a lack of strategy and a tax giveaway to those that frankly didn’t deserve it.

The basis of setting the Autumn Statement is therefore rather sombre:

The UK’s economic and fiscal outlook has deteriorated materially since March 2022. Higher inflation and interest rates, coupled with slower economic growth, have hit the public finances. Difficult decisions are necessary to put the public finances back on to a substainable footing in the medium term. This is the case across both taxation and public spending, and the government is adopting a balanced approach.

The Government claims that the Autumn Statement ‘sets out a clear and credible path to get debt falling and deliver the economic stability needed to support long-term prosperity.’ So what works within it?

GDP per capita past, present and future (OBR)

The talk before the statement was that there would be a significant cut in Research & Development spending – one of the most regressive measures the Government could have taken, given it already spends too little on helping to generate the nation’s future IP. Mercifully Research & Development funding hasn’t been cut, with a slight rise to £20bn of spending earmarked for 2024/25. As Steve Foxley, CEO of the University of Sheffield’s AMRC states, ‘this puts us in a competitive landscape with other countries….there are some good signals today.’ Our preference would have been for Government to go further and to review how this funding is dispensed – as Professor Richard Jones beautifully argues here – but this funding is essential for good growth and we are pleased it remains.

Secondly, taxation. We actually agree with the Government’s premise that ‘the fairest way to restore the public finances is to ask everyone to contribute a little, with those on the highest incomes and those making the highest profits paying a larger share.’ Windfall taxes – an increase on the profits of UK oil & gas companies (25% to 35%) and electricity generators (see below)– may annoy some shareholders but appears a fairer way of increasing tax take than other measures.

Where this falls down is that some renewables businesses will fall foul of the latter tax – a 45% levy on “extraordinary returns” on electricity sold above £75/MWh ($88.30/MWh), around a quarter of recent wholesale prices. Whilst it is ostensibly designed to stop companies benefitting from inflated power prices set by the gas market but without the need to actually pay for the fuel, we agree with green industry groups that see it as a disincentive for further investment – particularly when Oil & Gas companies taxed at a lower rate of 35% can offset the impact by making investments in new fossil activities – an option not available to power generators. The Government could insist on waiving this added tax if those companies invested in further green technologies, including privately funded Research & Development. We think they ought to tie up this loose end in future, whilst also further taxing those continuing to peddle gas and coal-fired electricity……

For a proper summary on all things tax, we defer (as ever) to Paul Johnson and colleagues at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Read their summary here.

Whilst it is unlikely that anyone in Government has read any of our previous reports on decarbonisation, the Chancellor has recognised that decarbonising property is both a key part of the country’s growth and in reducing emissions – hence the creation of a new Energy Efficiency Taskforce to reduce final consumption from buildings and industry by 15% in 2030 vs 2021 levels should be welcomed. It has set aside £6bn from 2025 to 2028 for this purpose. We’ll only be truly happy however if this is converted into a full-blown national retrofit programme, with funding devolved for local authorities to take forward on Government’s behalf….

Next, given the sudden jump in inflation and the projected decrease in living standards (see the last section of this report), providing some form of Energy Price Guarantee was frankly a necessity. As the IFS points out, the Chancellor has been helped by falling wholesale energy prices, which have reduced the cost of energy support measures for households and businesses. The energy price guarantee (EPG) for households announced on 8 September was set to cost £31 billion up to the end of March 2023, but is now expected to cost only £25 billion for that period. A less generous EPG will continue for a further 12 months (until end of March 2024), capping the typical yearly energy bill at £3,000 rather than the current £2,500 from April 2023. In total, the EPG is now expected to cost £38 billion over 18 months, whereas keeping it at £2,500 for 2 years as originally proposed by Kwasi Kwarteng would now be expected to cost £55 billion.

Finally, the Chancellor did the right thing by emphasising the Government’s role in funding and guiding infrastructure investment. The Chancellor highlighted infrastructure as one of three key growth priorities and said the government would “not cut a penny from our capital budget” within the next two years. Spending levels would also be maintained in cash terms for the following three years.

Although this means the government “is not growing our capital budget as planned”, it will still spend £600bn over the next five years, maintaining existing commitments to delivering the “core” Northern Powerhouse Rail scheme, the HS2 link to Manchester and to the Sizewell C nuclear power plant.

HS2 should be built out in full

As ever though, the devil is in the detail. The lack of quality East-West rail connections in the North is a national scandal and current pace, to use a motoring analogy, is still stuck in first gear. Similarly, HS2 should be built out in full and the Government remains eerily silent on what will happen to Phase 2b, now ending at East Midlands Parkway rather than the original plan to terminate at Leeds. Read our previous report on why this is a folly here.

THE BAD

Whilst a number of the steps above are reasonable or necessary, it still doesn’t add up to a coherent strategy from an admittedly new Government, continuing to point to a lack of new ideas or critical thinking within Government. It feels several ages away from Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of scientific revolution’ rhetoric of the 1960s, arguably the last genuinely progressive political strategy for the UK.

Worse, the Chancellor is storing up problems on a number of fronts. The macheting of Local Government budgets over the past dozen years has left a number of Councils teetering on the edge of administration and blighting local capacity on education, social care, highways and other key statutory services, leaving them little option but to ramp up Council Tax bills and to further reduce staffing. Every time this happens, local resilience gets gradually worse; the Government’s comments on spending across departments does not suggest they understand this conundrum:

To keep spending focused on the government’s priorities and help manage pressures from higher inflation, government departments will continue to identify efficiency savings in day-to-day budgets. To support departments to do this, the government is launching an Efficiency and Savings Review. This will include reprioritising spending away from lower-value and low-priority programmes, and reviewing the effectiveness of public bodies.

You cannot have good governance, administration or services in the UK – a bedrock of good growth – without resolute, well-funded local services. A new long-term settlement for local public bodies is long overdue.

Road taxes for EVs – a lack of joined up Government?

Next, the Chancellor announced plans to levy road tax on electric vehicles from 2025. This, like the plan to additionally tax renewable businesses, looks like a raid on developing sectors without understanding the implications of such a decision and we can well understand the frustration of the likes of Kia and Nissan that this could delay or deter customer adoption.

The Chancellor also removed the one decent bit of the Kwarteng mini-budget – the reduction of stamp duty! We reiterate our belief that stamp duty is a regressive tax and would rather it was completely abolished; increasing the burden of stamp duty tax on housing once again makes it harder for people to upsize, downsize or to move where better job opportunities are available.

There was also plenty missing within the budget – read on….

THE DOWNRIGHT UGLY

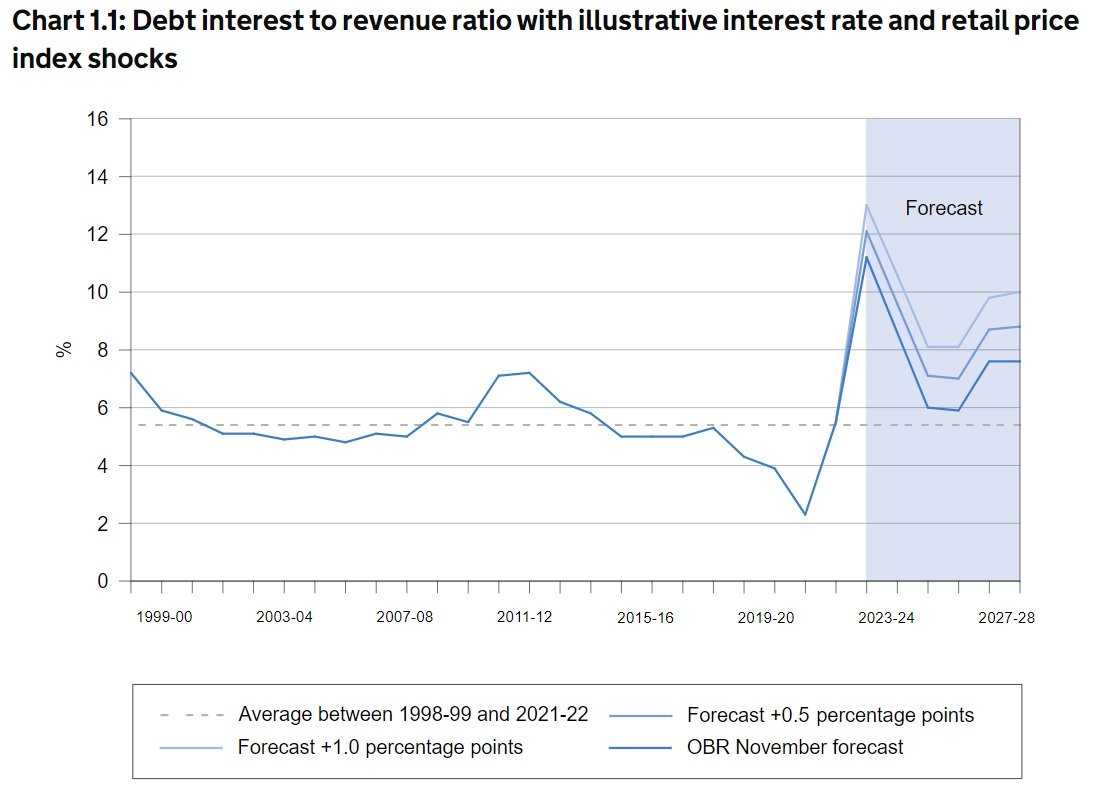

An admission from us. We had badly underestimated just how much the Government’s debt interest bill would be in future years. The OBR’s report reflects that debt interest payments will represent 11% of total revenues, the highest amount since the near-end of Wilson’s first Government of the 1960s. Just think what that money could go on (see local government settlement above…..)

Incredible spend on debt interest

The OBR expects spending on debt interest to reach £120.4 billion this year, the highest since the late 1940s, both as a share of GDP and as a share of revenue. If debt interest spending were a government department, its departmental budget would be second only to the Department for Health and Social Care. As set out in Chart 1.1, this year the government is expected to spend more than 11% of its revenue on debt interest, the highest level since the 1960s.

Let’s go onto two major issues that received no attention during the budget. You would not guess that we’re in the grip of a housing supply and affordability issue in the UK, yet there was no reference to housing anywhere in the statement bar energy efficiency. The same applies to planning, aside from the sensible decision to downgrade Investment Zones from their previous ‘Enterprise Zone on steroids’ carnations into a wish to work more closely with high-performing Universities to support their growth. A stable planning and housing system is a fundamental part of a strong economy, yet the Autumn Statement was as a mute as a trappist monk on either.

Finally, the major elephant in the room: immigration post-Brexit. For all the nonsensical talk in the budget of ‘grasping the benefits of Brexit’ (answer: there are none), the OBR’s one growth forecast related to increased skilled immigration – an essential element of future economic growth, given three quarters of firms have been hit by labour shortages over the past twelve months. The Chancellor appeared to admit this post-statement to ensure he does not need to go further than the £55bn of tax rises and spending cuts outlined in the Autumn Statement, whilst also hinting that the Government could even seek to soften the form of Brexit negotiated by Boris Johnson by removing “the vast majority of trade barriers that exist between us and the EU”.

At what stage does the rest of the Government follow this with the electorate to usher in a mature discussion about how we increase skilled immigration into the UK?

LEST NOT FORGET

Let’s go back to the basis of this statement. Whilst some of the action taken is both welcomed and essential, this does not prevent a difficult winter and months ahead for millions of people across the UK.

The Government’s own warning on this is stark:

Prices are rising faster than wages, an unavoidable consequence of the terms of trade deterioration. Adjusting for inflation, real wages fell by 3.7% in Q3. Households have started to cut back on spending in response, with retail sales volumes falling 1.4% in September to below their pre-pandemic level. Savings built up during the COVID-19 pandemic will have helped some households to withstand part of the shock, although these are concentrated predominantly in households in the top half of the income distribution.

Far worse is predicted by the OBR:

Unsurprisingly given the cost of living crisis, today’s Office for Budget Responsibility forecast suggests that this is going from bad to worse. This year we are set to see the largest fall in real household disposable income per head (4.3%) since the late 1940s; next year, we are set to see the second-largest fall (2.8%). Modest growth is expected to return after that, but even by 2027-28 we are not expected to have had a single year of growth higher than the pre-2008 average since 2015-16.

Year-on-year growth in real household disposable income over time (Source: IFS)

It’s easy to lose sight of what really matters within these overarching numbers so our overriding final message is a back to basics one. Above all else this Winter, be there for each other.