The Green Green Belts of Home

Coverage of the Green Belt across the UK

Building enough new homes in the right places is an evergreen economic and social priority for the UK. A cursory glance at recent national and local headlines reveal a holy smorgasbord of invective in doing this however…..

“Boris Johnson’s radical planning reform for housebuilding in England hangs in balance” (FT, 8 November)

“’Campaigners urge PM to prevent green belt allocations in draft plan’ (Planning Resource, November)

“Leicestershire district’s house building plans branded ‘unsound’ and ‘disturbing’” (Leicester Mercury, 11 November)

“The 190 homes by a Surrey golf course that’ll be built – but councillors say they’ve been ‘hoodwinked’” (Surrey Live, 11 November)

Headlines relating to planned new housing developments are often more likely if accompanied by references to them being built in the ‘green belt’ – a planning term that has entered into the mainstream consciousness in a way that its original meaning has been heavily altered, occasionally to the point of beatification.

Whilst the original basis of ‘Green Belt’ was sound and reasoned, its real world application often isn’t, acting as a clear inhibitor on the sustainable delivery of the 300,000 new homes the UK needs to build every year. Even worse, the politicisation and misuse of the phrase, often by people or groups who ought to know better, will act as a further brake on housebuilding in addition to reducing public confidence in planning and development.

This blog examines how this situation has come to pass, why ‘green belt’ often isn’t what you think it is and how actors including the Government could reform its use to accelerate the build out of new homes in the right places whilst engendering public trust back into the planning system.

Green Belt demonstration in Enfield

What exactly is the ‘Green Belt’?

The ‘Green Belt‘ in its most basic form “are areas around certain towns, cities and large built-up areas, where the aim is to prevent urban sprawl by keeping the land permanently undeveloped.” (RTPI)

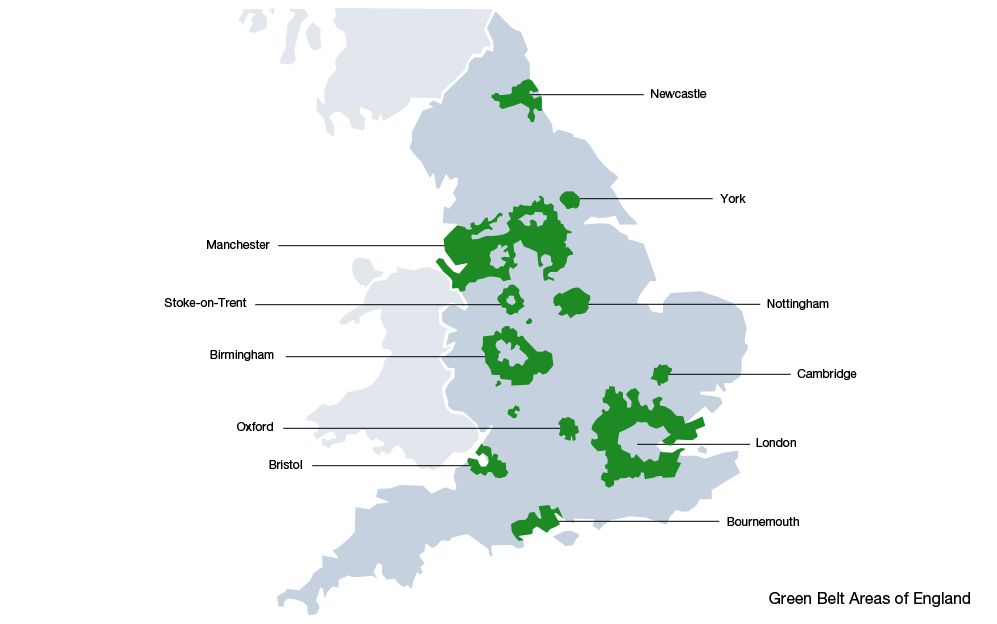

There are over a dozen green belts in England and their combined area (admittedly back in 2014) is over 1.6m hectares (>6000 square miles) or 13% of the land area of England. That last figure means it is inescapable to talk about planning new housing or commercial developments without any due regard to whether the Green Belt should be used.

Green Belts are a relatively recent phenomenon, with the idea first becoming statutory and reflected in the first county development plans of the 1950s; read the Conservative Government’s urge for county councils to establish green belts via this 1955 circular here. They were greatly extended via the County Structure Plans of the 1970s vis a vis local government reorganisation, and confirmed in the much missed Regional Spatial Strategies (RSS) of the start of this Century.

The original Green Belt Circular (in poor resolution), 1955

Following the abolition of both structure plans and RSS, green belts are now specified in individual local plans for local authority districts, boroughs or cities, with their production and review governed by the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

The NPPF states that the purpose of green belts are to:

· Check the unrestricted sprawl of large built up areas

· Prevent neighbouring towns from merging

· Safeguard the countryside from encroachment

· Preserve the setting and special character of historic towns

· Assist urban regeneration by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

This naturally draws the reader into asking “So what can you do with Green Belt land then?” The NPPF says that the following activities are “appropriate”……

· Provision for outdoor sport, recreation and cemeteries provided the development maintains the openness of the green belt

· Modest extensions to existing buildings

· Replacement of existing buildings

· Limited infilling in villages and limited affordable housing to meet local community needs

· Redevelopment of previously developed land provided it would not have a greater impact than the existing development (that last part is a particular source of debate between developers, local authorities and Government inspectors……)

Any other development is deemed to “inappropriate” and not supported. But what if local circumstances change, for example if housing supply lags well behind economic growth, creating a clear issue for employers and employees alike? The NPPF stresses that the designation or de-designation of green belts should only be made in exceptional circumstances through local plan reviews. This policy position allows local planning authorities to retain the same coverage of green belt but change the boundary by de-designating existing areas and designating other areas they deem more appropriate.

So…we have a restrictive policy to prevent urban sprawl, locally determined with reference to national guidelines. No wonder, as leading planning barrister Zack Simons opines, that the confusion starts with Green Belt’s name:

“It’s not all green and it definitely isn’t a belt. If greenbelt areas were called “urban containment zones” or something similarly unpoetic, more of us might understand what they are for.”

…but it’s this very lack of specificity that make it a highly effective political weapon in an age of cheap copy and local and national actors being known for what they’re against rather than what they’re for. Let’s have a look at a few recent examples.

Apparently humorous poster

The misunderstanding or misuse of the term ‘Green Belt’ is a regular feature

The following collection of comments and articles have been posted to show the passion and extravagance in language on the ‘Green Belt’ across the UK in its role in preventing urban sprawl, with all of them posted in the last three months. Whilst we offer neither support or criticism of each site referenced, the way the Green Belt is described does not improve public knowledge of what its role is, nor does it engender trust or provide constructive criticism of the present system:

EXHIBIT A

But if developers have their way, this prime plot of green belt land will soon be gone, flattened to make way for a new housing estate that by the end of the next decade could contain 330 homes.

“It would be horrendous for the local community if they build on here – particularly when you look at the sheer number of houses they are planning,” said Pam Haden, who lives on nearby Holcroft Road.

“As a green space it is so important for people’s health and wellbeing. Nobody wants to see it go. We hear a lot about how important it is to protect the environment and the green belt is supposed to be sacrosanct, yet they want to build on here.” LINK

EXHIBIT B (a particularly rancorous example)

‘Grab’ is another common word associated with Green Belt development

“That death knell for the Tory party is planning. Now neck deep in their ‘local plan’ policy madness, where swathes of previously sacrosanct green belt is now under serious threat from the concreters, they are doing little but upsetting their core voter base. Now the issue is not only the plans to annually build 300,000 unneeded homes across the UK (there are more than enough brownfield sites to plug the questionable gap), but the hypocrisy of those in government.” LINK

EXHIBIT C

In an open letter to Mr Johnson, the campaign group asks for the Government to step in and pause the current review of Shropshire’s local plan – which, if adopted next year as expected, will set out where more than 30,000 houses across the country will be built up to 2038.

The letter says: “Shifnal Matters welcomes your commitment during your recent conference speech, for building on brownfield sites first to protect our precious green fields up and down the country.

“Given the environmental effect house building has on the UK and the need to protect and enhance our ecosystem we agree that every brownfield site should be used before looking elsewhere.

“We trust that a robust list of all brownfield sites has now been compiled to prevent the unnecessary destruction of our countryside in the future. We would hope that Shropshire Council is able to draw on this list to avoid the decimation of our irreplaceable green spaces that are used and loved by all.” LINK

EXHIBIT D

Bovis Homes was given approval to build 117 homes on the former Sandwell Council campus in Pound Road in March 2010, but in 2012 the area was classified as a flood zone by the Environment Agency. In 2013, a planning application was granted to use part of the golf course on Heron Road to store and release flood waters.

Councillor David Fisher, leader of the Conservative opposition, said he welcomed the letter.

He said: “We’re calling for Sandwell Labour to adopt a brownfield first policy, which will allow us to build the homes we need whilst protecting our precious green spaces.

“Sandwell has countless brownfield sites left over from our industrial heritage. We must build on them to help redevelop the sites.” LINK

EXHIBIT E

But Mr French insisted it was local issues that dominated the campaign.

“My focus will now be delivering on those promises that I made during the campaign – get our fair share of London’s police officers, securing more investment for local schools and hospitals, protecting our precious green space,” he said. LINK

Type in ‘sacrosanct green belt’ or ‘precious green belt’ into Google and you’ll find hundreds of other similar references. These comments reflect:

• An increasingly fraught local planning system;

• An assumption that plentiful, available brownfield land exists somewhere in the UK to provide the new homes it needs (with that overall number subject to debate); and

• That the ‘Green Belt’ is impervious, beyond reproach and a haven of green space at the apex of ecological & social value.

Whilst there isn’t a great abundance of available brownfield land to build 300,000 homes a year on a sustainable basis (even the research of the CPRE – an avowed defender of the green belt from the development – estimates there is only just over three years worth of brownfield land for housing in this report), it is the third of these points that I take particular umbrage with. It is a damaging over-simplification to suggest that all Green Belt land should be automatically defended due to its ‘nature’, as green belt land in myriad places does not conform to this definition at all. The following example provides a fairly blunt rebuttal of what some believe Green Belt to be.

Daw Mill as cleared site, 2017

When the ‘Green Belt’ isn’t necessarily what you think it is

Daw Mill Colliery in Warwickshire was formerly the UK’s largest deep mine. Built as a UK superpit in the 1950s, it produced over 3m tonnes of coal per year at its peak. Sadly a major underground fire in February 2013 – the largest in UK mining history – brought the Colliery, and what was UK Coal, to its knees. Daw Mill shut its doors for the final time in 2013, with the site demolished by 2016. The UK’s last remaining collieries – Thoresby in Nottinghamshire and Kellingley in North Yorkshire – both closed in 2015, bringing to an end more than a Century of British coal production.

So why is this 112-acre, rail-connected former industrial site on this blog? Because dear reader, the site is classified as GREEN BELT. The site you can see on the right-hand side of this page, grey in hue with a rail connection less than 12 miles from the centre of Birmingham and with a significant amount of hard standing across its environs, is GREEN BELT.

This situation arose owing to the one of the conditions of the mine coming into operation – a restoration obligation, i.e. the need to restore the site to its previous condition – triggering the site into the Green Belt following the end of its working life as a mine. In planning terms, this means arguing that its development represents ‘very special circumstances’ in order to remove it from the Green Belt, either via a Local Plan Review or via the site owner making what is known as a departure application.

Now, I have an interest to disclose. I worked on the planning application and subsequent appeal for Daw Mill’s proposed redevelopment as a rail-connected employment site between 2013 and 2018. These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful and for full disclosure, you can read the final decision of the then Secretary of State here.

Three years after this decision, the site remains vacant and will remain so unless a Local Plan review removes it from the Green Belt. In my view, it is an enormous waste of a good site for rail-based employment (and let’s be honest, there aren’t many going round) but most critically of all, there are other sites similar in nature to Daw Mill across the UK that remain firmly rooted in the Green Belt, thus removing the opportunity to use them for future residential or commercial development.

Its sites like this that mean:

• Stating that all Green Belt sites are sacrosanct and must be protected due to their environmental or social value is a crass over-simplification that acts as an impediment to reasoned debate on the relative merits or drawbacks of individual sites; and

• Green Belt reviews, undertaken during the periodic review of each local authority’s Local Plan, is an essential element of making sure enough land is brought forward for residential or commercial development.

Local Government revenues 2010-2020 (courtesy of IfG)

How can thinking on (and talking about) Green Belt move on?

Grouping the Green Belt into a single homogenous deified entity, with no scope for sites to be used for either future housing or commercial development, is inherently flawed. How then do we move the conversation about Green Belt on, whilst maintaining the protection of sites that are of genuine environment and social value (such as National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty)?

Let’s get back to that issue of what it’s called. I agree with this quote from Planning House, which suggests going back to the drawing board to accurately reflect its purpose:

The name Green Belt brings up romantic images of England’s green and pleasant land, when in reality it is a strategic planning tool with an aim to restrict urban sprawl and encourage sustainable growth. Should the Green Belt be re-named the ‘Urban Containment Zone’, for instance, to better reflect such a purpose and technical function? I have had a personal gripe for many years with various people associating green belt with a landscape or environmental designation. Sadly the notion of Green Belt as a proxy for the countryside is not one that politicians are eager to dispel as it is a vote winner.

Let’s also go back to that man Zack Simons, who offers this lucid view in the FT:

The greenbelt has attained a mythic status in the imaginations of politicians. It is planning’s third rail — never to be touched. When the homeless charity Shelter proposed an element of building on the greenbelt (alongside other options) to meet London’s housing needs in 2016, their position was mischaracterised and there was a predictable furore.

It is unlikely that robust, intelligent conversation on the purpose and use of Green Belt in the public eye cannot take place until this name is given a well-earned shove, forcing people to look at what these land designations are actually there to do.

Now onto the next big issue – local planning authorities. Regularly reviewed and updated local plans must remain a central element of the planning system to keep control where it should be – locally. There appear to be at least three major issues to overcome however to build the right homes and commercial spaces in the right places:

1) Addressing the funding of local planning authorities. It’s been well documented that central government financial support for local councils has hugely reduced since 2010; the IfG notes here that Local Government ‘spending power’ – that is, the amount of money local authorities have to spend from government grants, council tax, and business rates – has fallen by 16% since 2010. The graph on the right shows this in more detail.

From first-hand experience, this reduction in funding has led to a marked reduction in staffing across a number of key service areas, including planning policy teams. This seriously impedes the ability of local planning authorities to review and implement up-to-date local plans, even before accounting for Government regularly altering what it wants from the local planning system….

The Government could address this in two ways. It could either increase Revenue Support Grants back into local authorities (unlikely given the Chancellor’s approach to spending) or it could provide ring-fenced grant support as part of its much-vaunted levelling up agenda to support sustainable growth. Either way, the current position cannot continue as it stands.

2) The Government should work constructively – but firmly – with those local authorities without an up-to-date local plan. A number of local authorities do not help themselves however with their long-term ‘slow’ approach to delivering local plans. Incredibly, St Albans Council’s current local plan was published in 1994, the same year Harry Styles, Tom Daley and Justin Bieber were born. Madness.

The unfortunate thing is that the Government is neither applying carrot nor stick to these local authorities with any consistency or regularity. In both 2017 and 2018, the then Secretary of State for DCLG threatened intervention in 15 local authorities; you can read his 2018 letter to them here. Councils like St Albans still do not have an updated local plan, whilst North East Derbyshire has only just adopted its plan four years later.

This problem is growing. Even at the start of 2021, Savills found that:

• 71% of local authorities have adopted an NPPF- compliant Plan – up from 58% in 2019 – but 40% of adopted NPPF- compliant Plans are over five years old and due for a review

• Six local authorities have withdrawn their draft local plans or had them fail at examination in the last year

Developing a more constructive approach with local authorities to accelerate effective plan making, including due consideration of the Green Belt, ought to be a priority for the rebranded Levelling Up, Housing and Communities department.

3) Are local authorities working to the ‘correct’ housing targets? Whilst Local Plans across the UK are currently mandated to deliver a housing supply in line with the Government’s standard method, I believe the UK needs to be more ambitious in the number of homes it needs to plan for. Chris Young QC beautifully summarises an extremely complex issue here (written when the Government was looking to change the method in 2020) and I wholeheartedly agree with his conclusions, which naturally has implications for the consideration of the Green Belt.

Are any of these suggestions likely to see the light of day? Noises from Michael Gove and his Ministerial team at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities suggest so, but the Government’s Planning Bill of suggested reforms will only be with us in early 2022 and as experience has shown, the devil will ultimately be in the detail…..

Not providing the 300,000 homes the UK needs every year – with the backlog continuing to grow – is a major social failure and addressing this thorny issue of Green Belt (sorry, Urban Containment Zones) must continually feature as part of the UK’s efforts to deliver. That man Mr Simons again to conclude:

In my work as a planning barrister, I see every day how our rigid approach to the greenbelt leads us into backward, unsustainable choices about how and where land is developed. The areas around our major cities are exactly where we need more development, not less, so that our homes are closer and more accessible to where we work, shop and socialise.

Green belts prevent sensible urban growth, which leads to the ever-expanding development of satellite towns further from where people already live and work. This adds up to more time spent in cars travelling to school, work or the shops. It also means greater pressure on building within cities and on the urban green spaces the public actually has access to (most greenbelt is private farmland).

A reform programme that sets out to solve our housing crisis without having a frank, grown-up conversation about the future of England’s greenbelt is one that is doomed to fail. (Read more HERE)

As always, listen to the experts

Unlike Michael Gove, I’ll never get fed up of experts and I recommend reading the works of at least three hugely talented and qualified individuals.

Chris Young QC is a sparkling planning barrister and is genuinely bothered about helping to resolve the UK’s lack of new housing supply. You can read his profile here and his dulcet tones on the excellent ‘Have We Got Planning News for You?’ podcast here.

The aforementioned Zack Simons is, in the words of 1980s band Jesus Jones, an ‘International Bright Young Thing’ who writes superbly on all manner of planning issues via the planoraks website. I can’t recommend his work highly enough.

Catriona Riddell is a town planner (and near neighbour!) who has just published, with the County Councils Network, a paper on the Future of Strategic Planning in England that suggests new arrangements to help ensure that local infrastructure keeps pace with new housing development and could assist with the government’s levelling up agenda. You can read the synopsis of the report and download it here.